Had the lecture been presented at the Magic Castle, rather than the Magic Circle, I’d say it is about the size of a soccer ball.

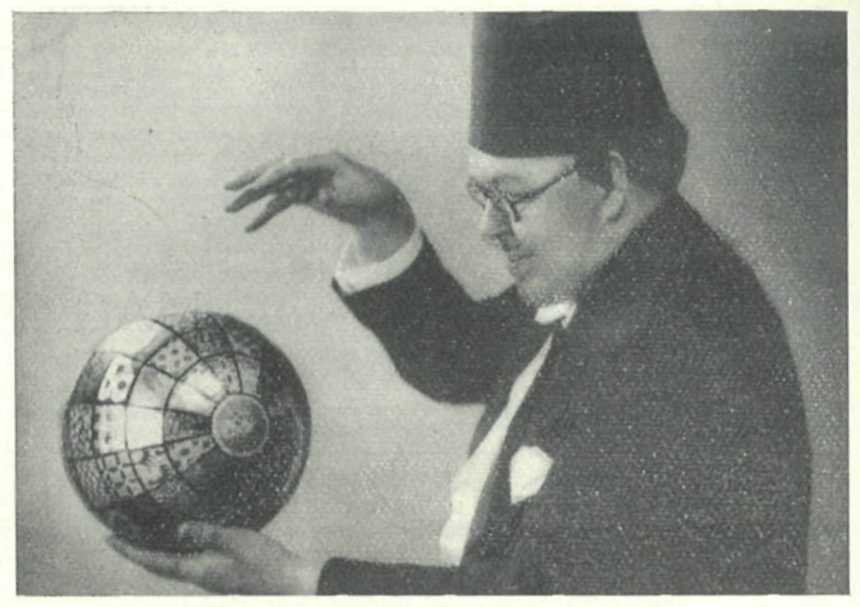

The caption under the photo reads: Charles Harrison, M.I.M.C with the Golliwog Ball.

Which begs the question; what the fudge is a Golliwog ball?

There you are, relaxed into your seat, one of 444 members of the audience in the Ambassador Theatre in London, having just enjoyed an interlude song-and-dance act. Now, England’s premier conjurer, David Devant returns to the stage for the second half of his 1916 Christmas spectacle.

The performance is documented in the Magic Circular.

Stage fully lighted. Curtain fit-up of black velvet and white lace.

A long board, resting on a chair back, running down towards footlights from mid stage. An

attendant holds a large ball, say, about 15 inches in diameter. Devant enters, takes ball and places it on upper end of board.

It commences to run downwards until he commands it to stop, which it does, and then rolls up and down the inclined plane, according to command.

He holds a large ring across its path on the board, through which it passes and repasses several times.

The explanation offered by Devant as to the obedience of the ball's movements is that a clown or golliwog is concealed inside it. But one doubts its exactitude, because the ball is obviously very light.

End quote.

This is the Golliwog Ball, a feature in Devant’s act which became one of his favourite openers and remained in his repertoire for over a decade.

It is clearly a linear development from the Obedient Ball, replacing the vertical cord with an inclined board. Devant saw it performed by Harry Kellar, using a suspiciously thick plank, and offered to create a better method in exchange for permission to perform it.

Devant developed his own method in 1903, which Kellar happily adopted. It also made its way into performances by Chung Ling Soo in the decade following. Our Hoffmann lecturer Charles Harrison was performing it in the 1950’s, having learned it directly through his personal friendship with David Devant.

A Golliwog, the implied driver of the ball’s movement, was a popular child’s toy in and around the UK for nearly a century. It was a rag doll with a racially exaggerated appearance similar to blackface minstrels. Over the course of many years, the word Golliwog developed into a racial slur. Fortunately, the character has since faded from popular culture.

This does not, however, explain why the magic trick might have faded. The presentational element of this little rag doll could just as easily be a goblin (as in Devant’s earlier script) or a tongue-in-cheek demonstration of physics, as it was presented by Charles Waller.

The effect seems to be checking many of the classic boxes here; We’ve got multiple performers, with unique presentations, spanning decades, incorporating a variety of practical methods to create a straightforward magical effect with a natural progression and climax.

This obedient ball was on a roll and then, suddenly, it stopped.

It seems to have vanished entirely from the stage by 1960, with the exception of Jim Steinmeyer presenting it once as an antique curiosity at the Los Angeles Conference on Magic History in 1992.

So why is this curious ball forgotten to all but magic historians? If it arguably shares all of Harrison’s qualities, why is it not immortalized as a classic of magic?

Humans seek the shortest path to success, and magicians, being mostly human, do the same.

Bringing a new routine on stage is a path full of hazards, and we don’t want to fall flat on our face in front of all those people. It’s natural to want to lower the risk of failure so we will feel safe.

Personally, I am a risky performer. I consider every show an experiment, and I’m willing to try new things just for the fun of it. Thankfully I don’t have much of a career to ruin.

I’ve had the experience, on more than one occasion, of digging up a long lost effect from an old book, putting it in my show, then other magicians in the area suddenly see the potential in that same old trick and add it to their repertoire. Purely a coincidence, I’m sure!

How many times have you gone back to a routine you’ve read before, in a book you already own, only after seeing it successfully performed by somebody else?

We’ve all done it. We saw it, we liked it, and we want a piece of their success!

The other magician got a great response with that trick, and you’re confident you can too.

It’s not wrong, per se, but it is lazy.

In my case I pulled a trick out of an old book because something about it appealed to me, but it was just one trick from hundreds of books and thousands of pages. Not so different from throwing a dart at my bookshelf and performing the trick it landed on.

When you do that same old trick simply because you saw me do it, you’re limiting yourself to my random pick when you could just as easily throw your own dart.

My theory is, if we trace back to the origins of the classics it would take us to an inspiring performance of a randomly chosen trick. It so inspired the second magician to perform it themselves, then the third.

It becomes this sort of relay race where each successive magician grabs the baton, whether passed to them or not, to carry the trick into their own performances. The long-lasting classics, it seems, are simply those relays which have managed not to drop the baton across the decades.

This survival of the most popular has given us hundreds of thousands of magicians who perform the same twelve tricks.

I encourage you to intentionally break the chain.

One trick, as Fitzkee suggests, is not inherently better than any other. They are recognized as “magic classics” only after they have been arbitrarily lifted above the rest.

It is the performance that makes the trick, not vice versa.

You can flip to your own random page in a random book and put your effort into performing the halibut out of that trick.

Enough with the magician see, magician do.

We’ll both benefit from having shows built from uniquely different material.

All of magic will benefit from an increased artistic diversity, and you will create a your own classic act, rather than an act of borrowed classics.

And with that we have reached the end of what will surely become known as a classic episode of Theory & Thoughts for Magicians. It’s got all the elements you could hope for; theory, thoughts, talking, and music.

I just need you to do your part, and tell everybody that this is a classic. If people hear it said often enough, it will become true. If it’s called a classic, new listeners will pay more attention, and imbue it with more value. My casual observations will be elevated to profound wisdom. It will become famous for being famous.

If you’d like to jump ahead of the crowd, you can subscribe to my temporarily un-famous weekly email newsletter at www.MagicTipsAndTricks.com